Debunking the “Latinx Vote”

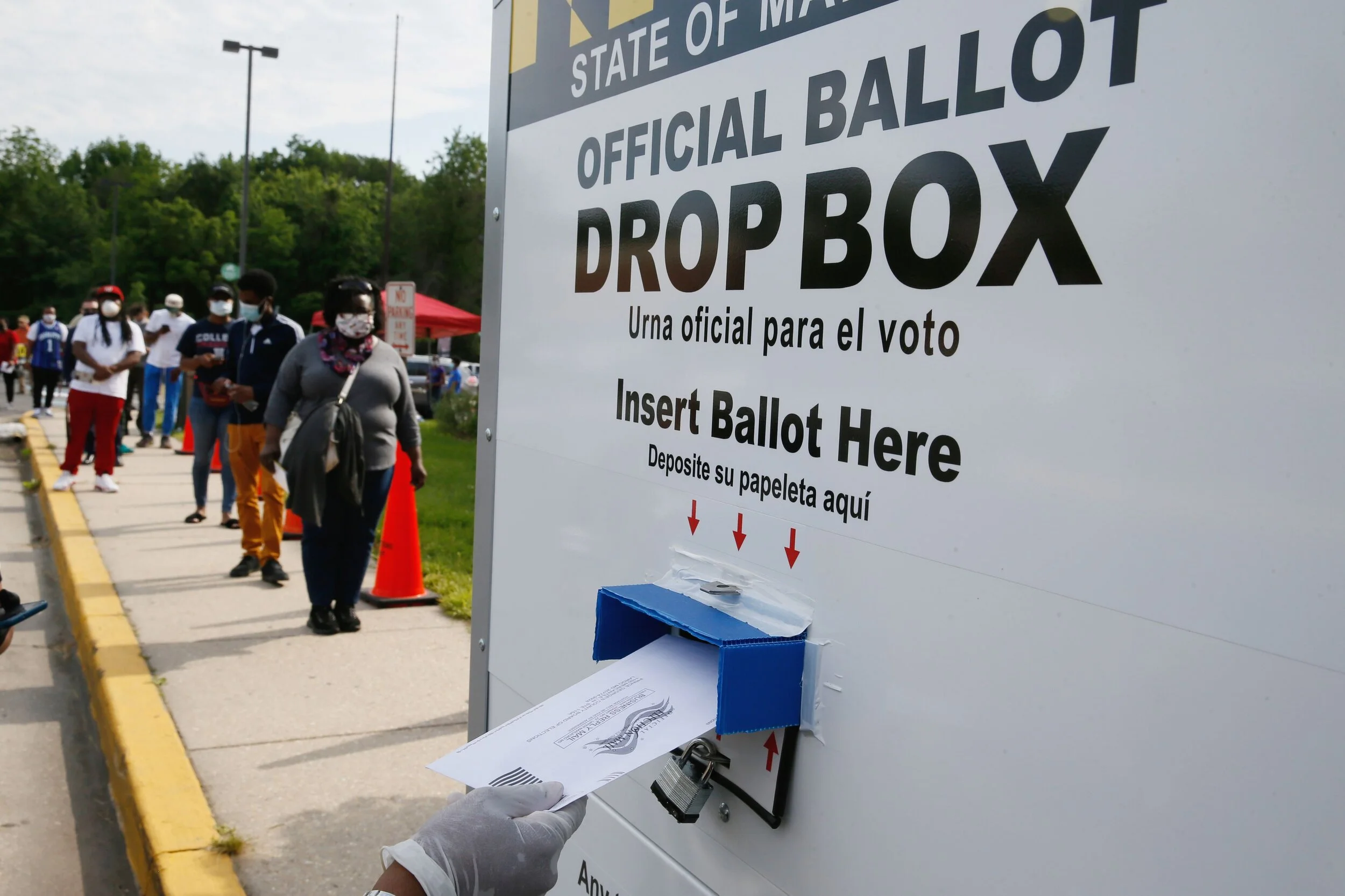

Voters in College Park, Maryland line up in front of a ballot box to cast their votes in the primary election. (Jim Bourg/Reuters)

The 2020 U.S. Presidential Election was not a regular election day for Americans. This year, the country knew that the results would not be confirmed that night, and no one knew when the winner would be declared. The nature of the election aligned with the nature of 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic has created unknowns for the nation and the rest of the world for the past several months. In the midst of not only a global health crisis but a racial pandemic, the divide in the nation was clear. With polar opposite presidential candidates, the biggest unknown was who the American people would choose.

One of the most disputed aspects of the election was the concept of the Latinx vote. News organizations and politicians spent weeks trying to predict who the members of this demographic would vote for. Many anticipated that Hispanic Americans would vote for now President-Elect Joe Biden, due to concerns on immigration and insensitive comments made by incumbent President Donald Trump. Others believed that President Trump would acquire the Hispanic vote, as large populations of the Latinx community lived in red states like Texas and Florida. By the time Joe Biden became the president-elect three days after Election Day, one thing was clear: there is no such thing as the Latinx vote.

Both presidential candidates appealed to the Latinx community, resulting in a large turnout of Hispanic Americans who voted Republican and Democrat. Assuming that an entire community predominantly votes a certain way insinuates that all members of these communities think the same and hold the same values. This could not be further from the truth.

Victoria Adler, an Argentinian freshman at UMD with an intended major in political science, shares her viewpoint on the idea of the Latinx vote and considers it a harmful narrative.

“Latinx people aren’t one dimensional and care about more than just immigration policies … We aren’t monolithic; we are complex, diverse, and we disagree just as much as any other minority [group],” Adler stated.

Senior government and politics major and member of the Political Latinxs United for Movement and Action in Society organization at UMD, Julián Pérez-García, expands on this viewpoint.

“As a third-generation immigrant, my voting habits are not very influenced by personal experience with immigration,” Pérez-García said.

While Pérez-García chooses to vote based on “human-centered and compassionate immigration policy,” he also acknowledges that there are “cultural and ideological issues” that highlight many differences within the Latinx community and lead them to vote differently.

While the 2020 Presidential Election has caused a lot of confusion, it has definitely clarified why the idea of the “Latinx vote” is flawed. Record voter turnout from this demographic and many others has shown that the American people are diverse in political opinion. Hispanic and Latino Americans hail from many nations and identify with many different races and communities, which is reflected in the different ways they vote.