Can Non-Black People Use AAVE?

African American Vernacular English, or predominantly referred to as “ebonics,” is a term popularized by the black community that often conjures a sense of familiarity and comfort amongst one another.

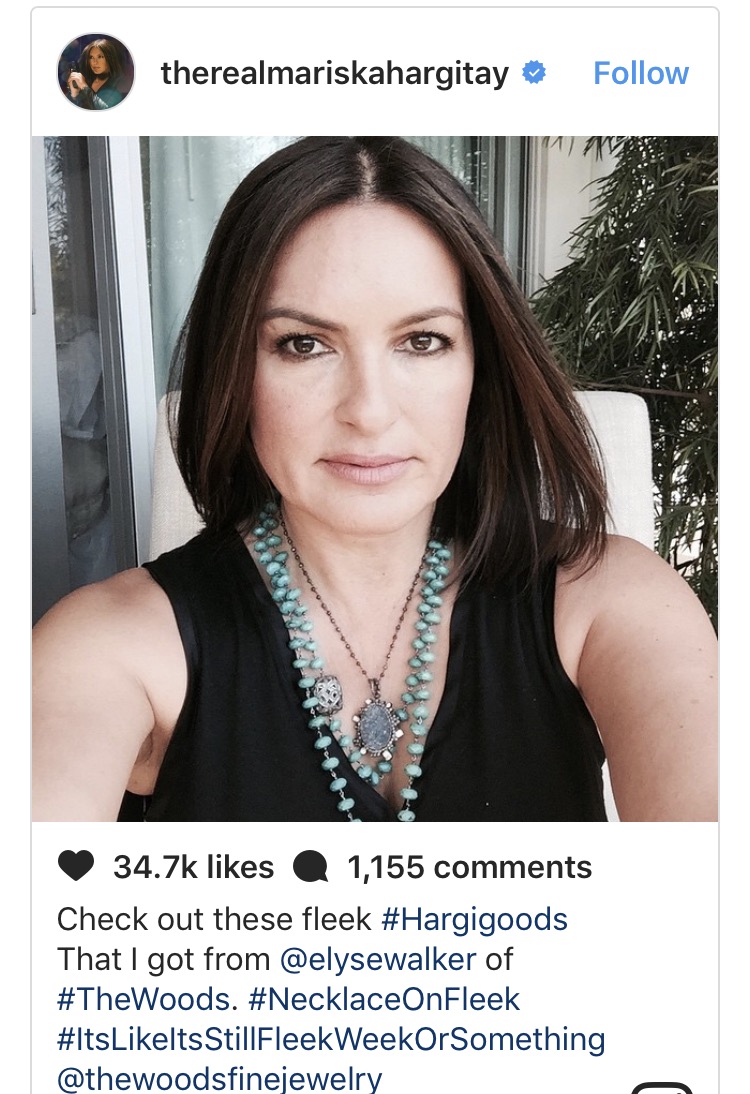

Words and phrases comprised of “ight,” “finna,” and “fleek” are often displayed through social media sites such as Instagram and Twitter, and inevitably adopted by a greater audience as it begins to infiltrate the scripts of television series, clothing brands and the jargon of entertainment news reporters with expectations of appearing more, “hip with the times,” “gangsta” or “trendy.”

Moreover, the association of ebonics with criminality reiterates preconceived notions of inferiority cultivated by repetitive media misrepresentation and memorialized through government policy. This association is further exacerbated as it is often used to justify violence against black people and exemplifies how the use of ebonics to appear more intimidating influences public perception. In addition, the dissemination of ebonics as “fashionable” commonly emerges as white celebrities “discover” terms of black slang that predate their existence and are quickly deadened from overuse within the general public.

It is particularly frustrating when these terms are adopted with little to no understanding of its proper use and employed as a source of profit by corporations. Such as in the case of Kayla Newman, who coined the phrase, “eyebrows on fleek,” amassed the attention of celebrities, social media users, and companies that slathered it across their products without her permission nor recognition of her creativity.

Innately tied to the black experience, non-black people who argue that AAVE is simply, “a cool way to speak” or that, “everyone talks like this” deny the significance of black language and its history of bridging socioeconomic gaps and fostering an identity within the black community.

Here is an example of how non black people often adopt AAVE without an understanding of how to properly use it.

Furthermore, it is akin to mimicking a culture of people who have been consistently oppressed and denied opportunities for speaking in a manner that is now deemed acceptable for whites and non-black people to use. However, when it is used by its originators it is denounced as, “ghetto” and in alignment with negative portrayals of black people. Although ebonics is frequently conflated with uneducated black youth, a manifestation of America’s disconcerting history and prevailing tensions with the black community, the ubiquity of ebonics is not restricted to particular economic standing.

Ebonics is recognized by the vast spectrum that is the African diaspora and is intrinsic to black culture regardless of economic or social boundaries. Consequently, when words and phrases coined by the black community are commercialized and misinterpreted by a largely white audience that refuses to acknowledge its origin, black language is being appropriated and that is not okay.